JGA

This is a blog about what it’s like to be an English professor and to be a member of the Rockhurst community, which is to say that it's a blog about things that are awesome.

Monday, April 20, 2015

on lists (on Yom HaShoah)

I just walked across the quad to my office. I'm teaching Walt Whitman today. It's Yom HaShoah. A list of names is being read over a PA.

I’m fascinated by roll calls. Lists of proper names carry a dense sheen of reality: grade-school rosters, the granite-etched names of casualties at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in D.C., the names I hear read over a PA on the quad as I walk to my office. Lists can be a concordance of common experience. They can be the ties that bind Americans to what passes (sometimes) for a union.

We probably owe the impulse to unify by listing to Walt Whitman, whose catalogues are famously democratizing. They capture the simultaneity of civic space; the comings and goings of prostitutes and presidents alike are contemporaneous. So are slurs. Placed together, “Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff” become an alliterative nickname train.

Whitman’s poetry counteracts the otherwise evaluative nature of recounting. When we only call out the names, when we generate a composite list that is not (yet) resolved into a system of subordination that sorts out the somewheres from the elsewheres, we invite the visceral experience of democracy.

But of course, Whitman was as much a New York poet, praising “Mannahatta,” as he was the roughneck of the original frontispiece of Leaves of Grass.

Even the most democratic listing strategy becomes hierarchical, especially in the U.S.

I remember how heartbroken I was to learn that the vamp verse at the end of Huey Lewis’s song, “Heart of Rock and Roll” (1983) was tailored to regional markets. While all versions of the song included the line “D.C., San Antone, and the Liberty Town, Boston, and a Baton Rouge. Tulsa, Austin, Oklahoma City, Seattle, San Francisco, too,” and whole verses about “New York, New York” and “LA, Hollywood,” the pairs of cities that follow “in Cleveland … Detroit!” change from market to market. While I heard “Chicago … Kansas City!” at the song’s finale, other Midwestern markets heard Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, or Milwaukee.

Adjacency always leads to subordination; the mapmaker has to place the compass rose somewhere, and that somewhere is always an elsewhere. Always a Hoboken.

Friday, April 3, 2015

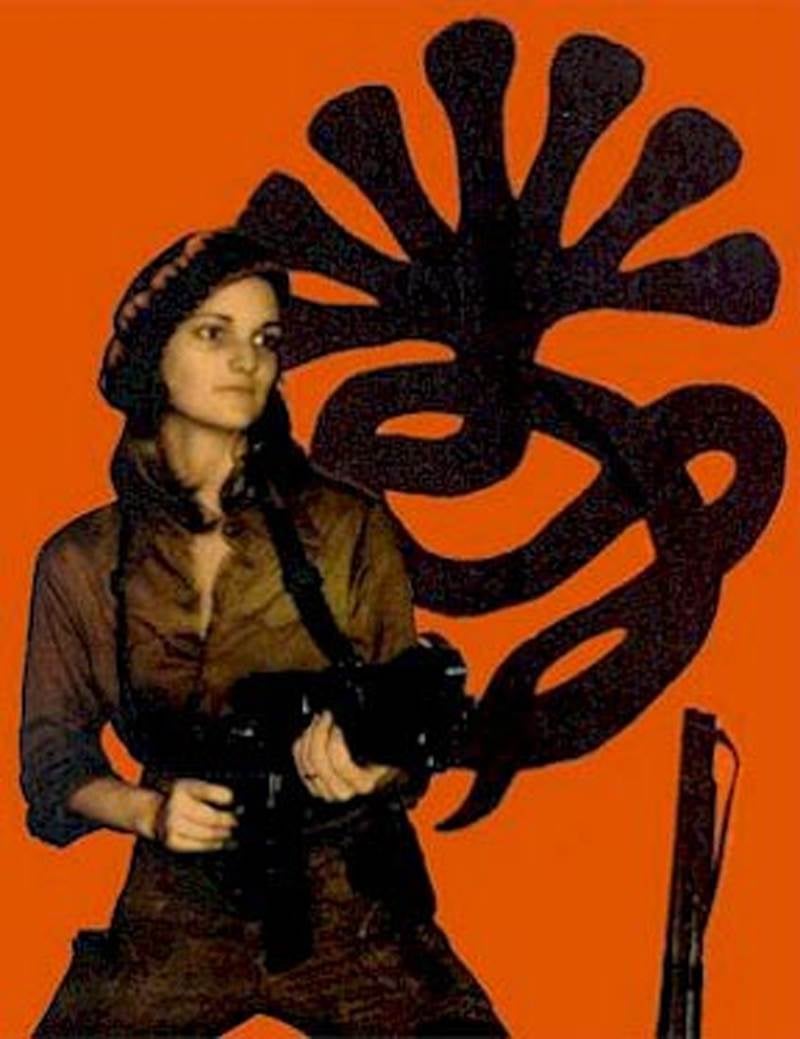

The Kids of Today Should Prepare Themselves for the Seventies

images courtesy of the EPA's Documerica project (1971-1974)

I put up these fliers advertising a course I’m teaching in the

fall, about the legacies of the 1970s, and students have been asking questions. Why are the 70s so big right now?

Here are some reasons why I decided to draw my American Literature Since 1945 course into the vortex of that polyester decade.

Here are some reasons why I decided to draw my American Literature Since 1945 course into the vortex of that polyester decade.

First off, this song by Mike Watt and Eddie Vedder has been

one of my favorites for going on two decades:

Also, why wouldn't we want to spend a semester

examining the art and fiction of a decade that included the resignation of

Richard M. Nixon,

the fall of Evel Knievel,

the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam,

the arming of Patty Hearst,

the bombing of the State Department by the Weather

Underground, and the Roe v. Wade

decision. Not to mention all those cringeworthy fashion and design trends.

But quirk and kitsch are not the decade’s only sources of

allure. I'm teaching the course, in part, because I want to get to the bottom of why so many Instagram filters make digital photos look like Polaroid pictures and why, last Christmas as my family sifted through old photo albums,

my twentysomething niece, when she found a photo of her mother drenched in the analogue crepuscularity of a seventies sunset, vowed to start a band just so she could use that photo as an album cover.

My hunch is that 70s are important to fiction writers today because a 70s setting is an ideal backdrop through which to imagine a way

of being in the world that feels granular, like the opposite of the interface-fractured conveyor belting we do these days. In

explaining why she wrote her seventies-set novel, Rachel Kushner admits to

finding irresistible the “particular, slightly romantic glow” of its gritty

mis-en-scène.

Another reason why the 70s are magnetic now is that it's the last decade where young people got to live the life of the mind without having to feel like freaks. American

triumphalism was asleep during that decade. We hadn’t yet elected the Hollywood movie

star who single-handedly change the point of college from

it’s-where-you-go-to-develop-a-meaningful-philosophy-of-life to it’s-where-you-go-if-you-want-to-be-well-off-financially.

Look at this graph that measures student rankings of various objectives for attending college. At the start of the 70s, fewer than 40% answered “Being very well off financially” and almost 70% answered "Developing a meaningful philosophy of life." Today, those percentages have pretty much flipped.

So part of what makes me optimistic about 70s nostalgia is the possibility that it’s actually a nostalgia for a time when one wasn't scorned for wanting to organize her life around some principle other than financial gain.

Which is to say that the seventies are to this English professor as the fifties are to his mother. It is a magical decade in which radical political change was still possible, anyone could live in SoHo, and an heiress might take up arms against the pigs.

Look at this graph that measures student rankings of various objectives for attending college. At the start of the 70s, fewer than 40% answered “Being very well off financially” and almost 70% answered "Developing a meaningful philosophy of life." Today, those percentages have pretty much flipped.

So part of what makes me optimistic about 70s nostalgia is the possibility that it’s actually a nostalgia for a time when one wasn't scorned for wanting to organize her life around some principle other than financial gain.

Which is to say that the seventies are to this English professor as the fifties are to his mother. It is a magical decade in which radical political change was still possible, anyone could live in SoHo, and an heiress might take up arms against the pigs.

Here's a possible reading list for that 70s course:

Louise Meriweather, Daddy

Was a Number Runner (1970)

Nicholasa Mohr, Nilda (1974)

Jonathan Lethem, Fortress

of Solitude (2003)

Dana Spiotta, Eat the

Document (2006)

Junot Díaz, The Brief,

Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007)

Sean McCann, Let the

Great World Spin (2009)

Rachel Kushner, Flamethrowers

(2013)

Thursday, February 27, 2014

Shameless Plug for an Amtrak Writer's Residency Starts in ¶ 3

“Hobokens and Cuautitláns of the world, unite!”

I recently, actually put that tortured allusion in a call for papers for a journal issue that I’m guest editing. The topic is “Elsewheres,” and I want it

to be a bunch of great essays about the art that is made in and about places

that are emphatically not capitals of

the world. (“Cuautitlán” was a Chilango’s answer to the question “What is the

Hoboken of Mexico City?”) I got the word “elsewheres” from a talk Junot Díaz

gave at the University of Kansas. Díaz referenced Robert Smithson, who talked

about the art world as being split into “somewheres” and “elsewheres.”

Elsewheres are where art gets made and somewheres are where art goes to become

important.

I want the issue to be a kind of coalition of elsewheres, a

reminder of how much peripheral places have in common, which is to say that I want the issue

to have an agenda (why else leave in a winsome nod to Marx and Engels?). I

want the issue to give an intellectual dimension to my conviction that with the

twenty-first century ought to come an end to the unequal distribution of

cultural authority. I want to make explicit the consequences of continuing to

rely on a system whose generators of value and engines of public opinion are all

packed into the same few somewheres.

I’m very excited about the issue. But I need Amtrak to give me

a Writer’s Residency. I need to write the introduction while traveling

over the connective tissue between elsewheres and somewheres. I need to board

the Southwest Chief in Kansas City and ride it all the way to Los Angeles.

Rail writing will provide me an everywhere from which to theorize about the how the axes of sway might

change in the twenty-first century, about whether New York or LA will ever be

irrelevant, or if such an idea is too fantastic, the stuff of zombie novels and

post-apocalyptic action movies. As fantastic as an Amtrak writer’s

residency.

I want to my ideas about these big questions to take shape while

I move through the elsewheres of the American narrative, while I glimpse Wyatt

Earp Boulevard in Dodge City or pace the fast lane of Route 66. The train offers

the rare experience of seeing America’s elsewheres on their own terms, as it enlivens

the common ground that connects them.

Sunday, January 19, 2014

East Side, West Side

I’ve been re-watching Ric Burns’s New York documentary. During

episode three, which is about the late-nineteenth century (from Boss Tweed’s

rise to power to the consolidation of the five boroughs), I dozed off and was awakened sometime later by an eerie, a cappella voice singing the

lyrics of “The Sidewalks of New York.”

The lyrics “eeeeast siiiiide, weeeest siiiide, aaaaaall aaaroooound

the toooown” whispered as they were into my sleeping ear iced my brainstem, and the waltzy melody merged enough with the

rhythm of my own breathing so that, for a second, I thought the dirge was coming

from my own body, that I was an engine of nostalgia for a song about a city I’d only ever

really been to once, a city whose monopoly on cultural trusteeship I'd never been quite happy about.

That whisper in the ear and the inception about old New York

that came with it created a micro-moment of melancholy. I opened my eyes. I

couldn’t quite focus on the old photos panning slowly by, Burns style. By the

time the part of the song that includes the line about “tripping the light

fantastic” came around, I was awake and knew had been a victim of emotional

manipulation. I put my glasses on, got back to work.

What struck me about the song was how like Celtic music it

was. How awfully its singer wanted me to want preserved in song the bygone era

his lyrics embroidered. The part of me that doesn’t wear green on St. Patrick’s

Day and that winces when I hear stories about happy, hospitable Irish people—stories

about tourists finding confirmation of their own preconceptions—said “bleck.”

But the nostalgia that that song so assertively conveyed was

different from the Thistle and Shamrock schmaltz

I’d dodged so often on so many NPR Sunday afternoons. I noticed that “The

Sidewalks of New York” makes a lot of references to specific people and places.

There are the names of the boys and girls who had taught the singer how to

dance and what to play in the streets, boys and girls who had long since vanished

into various corner of America. It was the kind of referencing that makes me

love Tom Waits songs, like this one

Johnny Casey, Jimmy Crowe, Jakey Krause, Mamie O’Rourke, Nellie

Shannon, and Tony—this kind of hood-rat roll call always warms my heart. It carries

the kind of dense verisimilitude one might find on an old grade-school class roster. The

academic in me paused at the naming of “Jimmy Crowe”—is that some cryptic

reference to nostalgia for segregation? I did some

rudimentary research (that is, I googled “The Sidewalks of New York”).

A popular vaudeville number in the 1890s, “The Sidewalks of

New York” became somewhat canonical piece of Americana. It had been recorded by the likes

of Duke Ellington and Mel Tormé and had even been echoed in two early Fleischer

cartoons (one made

in 1925 and one in 1929). This ubiquity excited me. I’m teaching Edith

Wharton’s The Age of Innocence and I immediately perked up at the

fact that more makers of culture than Wharton had been, in the 1920s, thinking

about late-nineteenth-century Gotham. A youtube clip of either of those cartoons

would have offered an excellent lowbrow contrast to Wharton’s novel--would have made for great class-time discussion fodder. Alas, I

could find neither cartoon. But, I did find this Fleischer 1935 production:

That got me thinking about that Uncle Tupolo song, “New

Madrid,” with the line “they all come from New York City.”

The fact that New

York is the port of entry for so many ancestors of red-state citizens is good barb to use against unsuspecting New York haters. Like these guys…

Benign and incidental as it may be,

the fact that the sidewalks of New York constitute the earliest, most

sepia-toned memories of America that most European immigrants can call

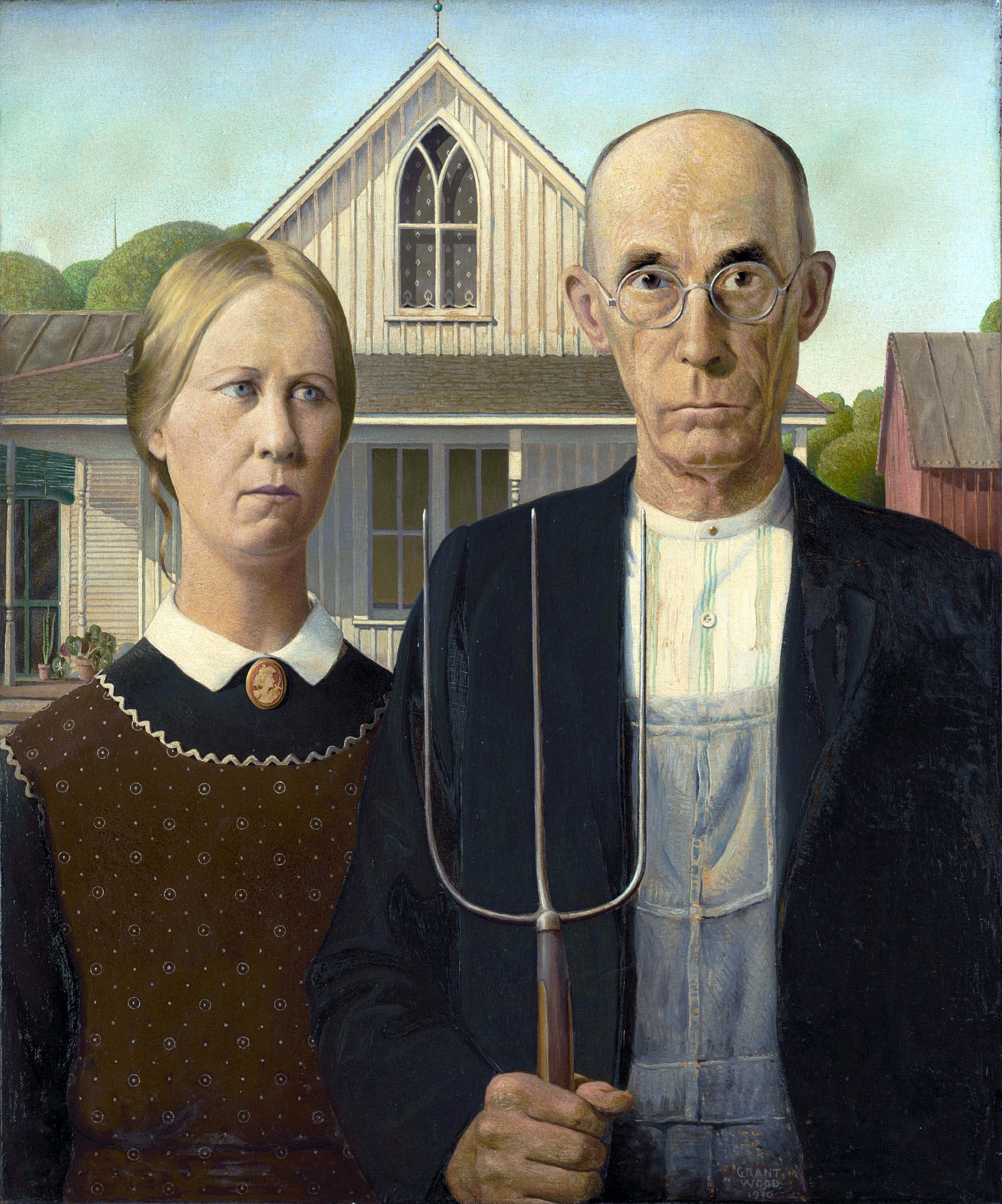

up is worth pondering. Maybe that pitchforked old man in “American Gothic,” you

know the one,

is thinking about the hurdy-gurdy man on the corner Hester

and Bowery in the Lower East Side, not the wheat and milk-cows of the prairie. Maybe the capitals of

the world really are our fathers.

If so, I’m that much closer to getting why my uncles love Bruce

Springsteen, why his ballads of sainthood in the neighborhoods of the Jersey Shore ring so true them, boys who grew up in the Irish-Italian ward of Kansas

City. There may have still been some traces of the blue-collar, urban

sensibility of Springsteen’s lyrics in the streets of the northeast Kansas

City when my uncles were young. Maybe sidewalks of New

York once extended all the way out to middle America.

It's the suburbs that severed the link to New York, that repackaged our stereoscopic birthrights into the bright lights, big city skyline posters and the “I <3 NY” T-shirts we all ignored on our way to the Orange Julius stand.

It's the suburbs that severed the link to New York, that repackaged our stereoscopic birthrights into the bright lights, big city skyline posters and the “I <3 NY” T-shirts we all ignored on our way to the Orange Julius stand.

The ties that bind red and blue America are buried somewhere beneath the shopping malls of our youths.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_tif.jpg)