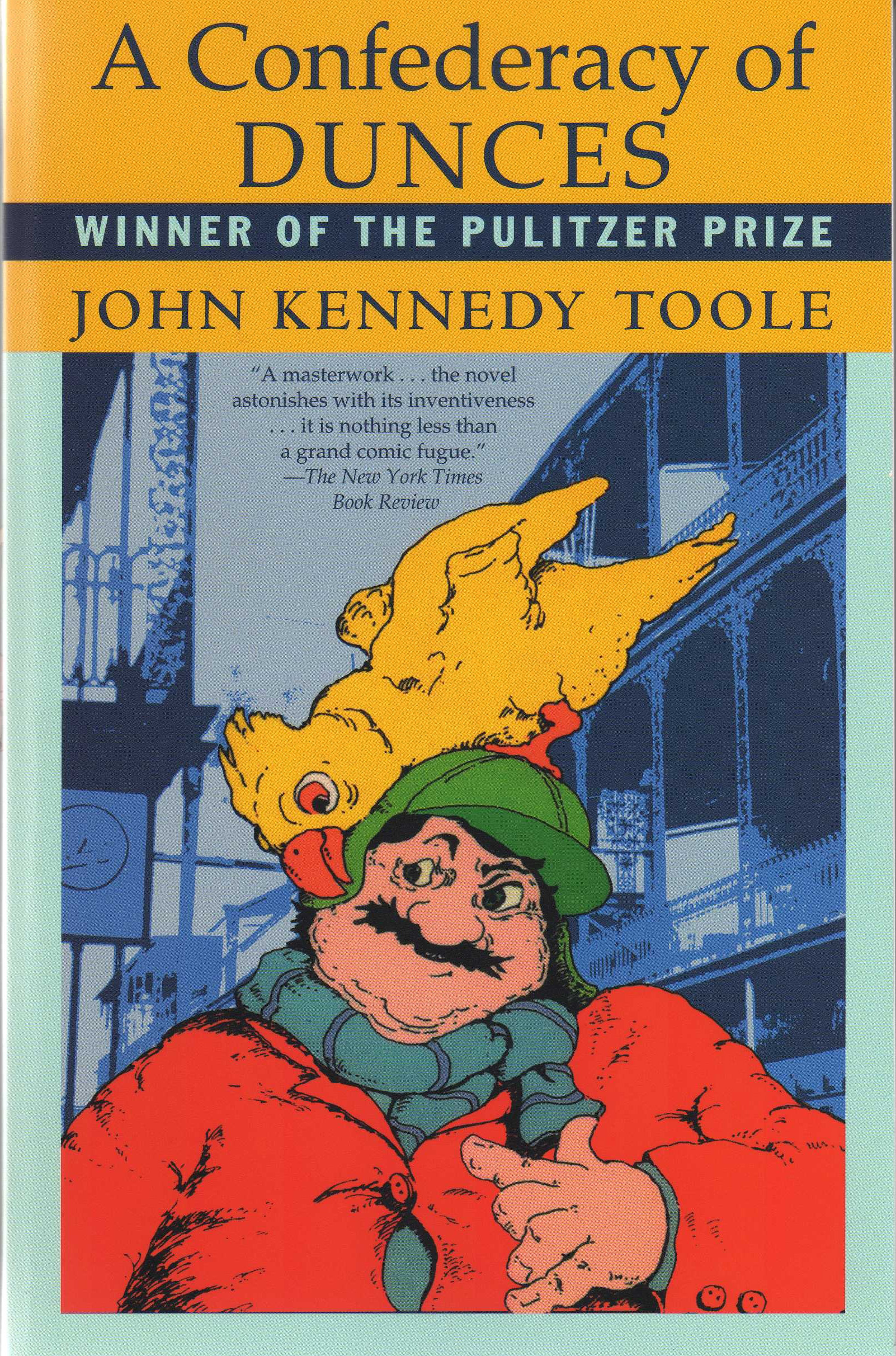

For their first

paper of the semester, students in my American Literature Since 1945 class have

to treat an intensely funny novel as though it might be dead serious.

This is the kind

of novel whose main character is so impossibly hilarious that the filmmakers who

have tried (and failed) to make movie version of him can only think of top-brass

funnymen to fill the role: Harold Ramis chose John Belushi in the 1980s, in the

90s the names were John Candy and Chris Farley, in the early 00s David

Gordon Green picked Will Farrell. Now it’s The

Muppets James Bobin in the director’s chair and (drumroll) Zach Galifianakis

in the role Ignatius J. Reilly.

Galifianakis is the right man for the job. He is funny in

a way that scares me a little, that inspires equal parts pathos and

schadenfreude.

Students have to

answer the question of whether A Confederacy of Dunces is

a “Civil Rights novel” or not. By “Civil Rights Novel,” I mean a novel that is committed

to solving such big American problems as racial segregation, to doing something more than turning such problems into a literary enterprise.

Confederacy is a good candidate

for this kind of investigation. Like

Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Confederacy is

a novel whose light-hearted fun masks a more complex statement about race

relations in America. Critics have long disagreed about what effect Twain’s book has on

race relations, and on whether the author had any philanthropic motivations at

all. This edition of Huck Finn collects all the relevant essays of that critical controversy.

One of the things

students have to do is track the novel’s representation of political activism,

as such scenes can offer insight into the author’s impressions of the civil disobedience happening in the American South at the time he wrote

the novel.

To that end, and in

honor of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, I offer this very brief roll call of early Civil

Rights-era actions:

In 1955, there is a bus boycott in

Montgomery, Alabama, wherein African American citizens of Montgomery refused to

ride city busses, thus reminding the city how much it depends on the revenue

of citizens it forces to the backs of its busses. The boycott is lifted a year

later, after the U.S. Supreme Court declares Alabama’s bus segregation policy

unconstitutional.

In February

of 1960, four black college

students in Greensboro, North Carolina, sit down at a “whites only” lunch

counter and order coffee. When refused service, they refuse to leave. Thus the

“sit-in” is born in the American South. Many restaurants are desegregated as a

result.

Student Nonviolent Coordinating

Committee (SNCC) was also founded in 1960.

In 1961, organizers in the North

stage “Freedom Rides,” in which college students travel South in buses to test

the effectiveness of a U.S. Supreme Court decision that desegregated interstate

bus stations. When the Freedom Riders reach Alabama, violence erupts.

In 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr.

leads antisegregation marches in Birmingham, Alabama. Police attack

demonstrators with dogs, and firefighters turn high-pressure water hoses on

them. Television broadcasts of the violence shocked the nation, increasing

support for civil rights.

Later that year, national civil

rights leaders stage a “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” at which

King delivers his “I Have a Dream” speech to an audience of more than 200,000.

In 1964, the SNCC recruits Northern

college students to help register voters in Mississippi. The project received

national attention when three participants were murdered.

In 1965, at an SNCC protest in Selma,

Alabama, police beat and tear-gas marchers. Televised scenes of the event shock

create broad support for a law to protect African Americans in the South who

want to exercise their right to vote.

In 1968, King is assassinated in

Memphis, Tennessee.