I’ve been re-watching Ric Burns’s New York documentary. During

episode three, which is about the late-nineteenth century (from Boss Tweed’s

rise to power to the consolidation of the five boroughs), I dozed off and was awakened sometime later by an eerie, a cappella voice singing the

lyrics of “The Sidewalks of New York.”

The lyrics “eeeeast siiiiide, weeeest siiiide, aaaaaall aaaroooound

the toooown” whispered as they were into my sleeping ear iced my brainstem, and the waltzy melody merged enough with the

rhythm of my own breathing so that, for a second, I thought the dirge was coming

from my own body, that I was an engine of nostalgia for a song about a city I’d only ever

really been to once, a city whose monopoly on cultural trusteeship I'd never been quite happy about.

That whisper in the ear and the inception about old New York

that came with it created a micro-moment of melancholy. I opened my eyes. I

couldn’t quite focus on the old photos panning slowly by, Burns style. By the

time the part of the song that includes the line about “tripping the light

fantastic” came around, I was awake and knew had been a victim of emotional

manipulation. I put my glasses on, got back to work.

What struck me about the song was how like Celtic music it

was. How awfully its singer wanted me to want preserved in song the bygone era

his lyrics embroidered. The part of me that doesn’t wear green on St. Patrick’s

Day and that winces when I hear stories about happy, hospitable Irish people—stories

about tourists finding confirmation of their own preconceptions—said “bleck.”

But the nostalgia that that song so assertively conveyed was

different from the Thistle and Shamrock schmaltz

I’d dodged so often on so many NPR Sunday afternoons. I noticed that “The

Sidewalks of New York” makes a lot of references to specific people and places.

There are the names of the boys and girls who had taught the singer how to

dance and what to play in the streets, boys and girls who had long since vanished

into various corner of America. It was the kind of referencing that makes me

love Tom Waits songs, like this one

Johnny Casey, Jimmy Crowe, Jakey Krause, Mamie O’Rourke, Nellie

Shannon, and Tony—this kind of hood-rat roll call always warms my heart. It carries

the kind of dense verisimilitude one might find on an old grade-school class roster. The

academic in me paused at the naming of “Jimmy Crowe”—is that some cryptic

reference to nostalgia for segregation? I did some

rudimentary research (that is, I googled “The Sidewalks of New York”).

A popular vaudeville number in the 1890s, “The Sidewalks of

New York” became somewhat canonical piece of Americana. It had been recorded by the likes

of Duke Ellington and Mel Tormé and had even been echoed in two early Fleischer

cartoons (one made

in 1925 and one in 1929). This ubiquity excited me. I’m teaching Edith

Wharton’s The Age of Innocence and I immediately perked up at the

fact that more makers of culture than Wharton had been, in the 1920s, thinking

about late-nineteenth-century Gotham. A youtube clip of either of those cartoons

would have offered an excellent lowbrow contrast to Wharton’s novel--would have made for great class-time discussion fodder. Alas, I

could find neither cartoon. But, I did find this Fleischer 1935 production:

That got me thinking about that Uncle Tupolo song, “New

Madrid,” with the line “they all come from New York City.”

The fact that New

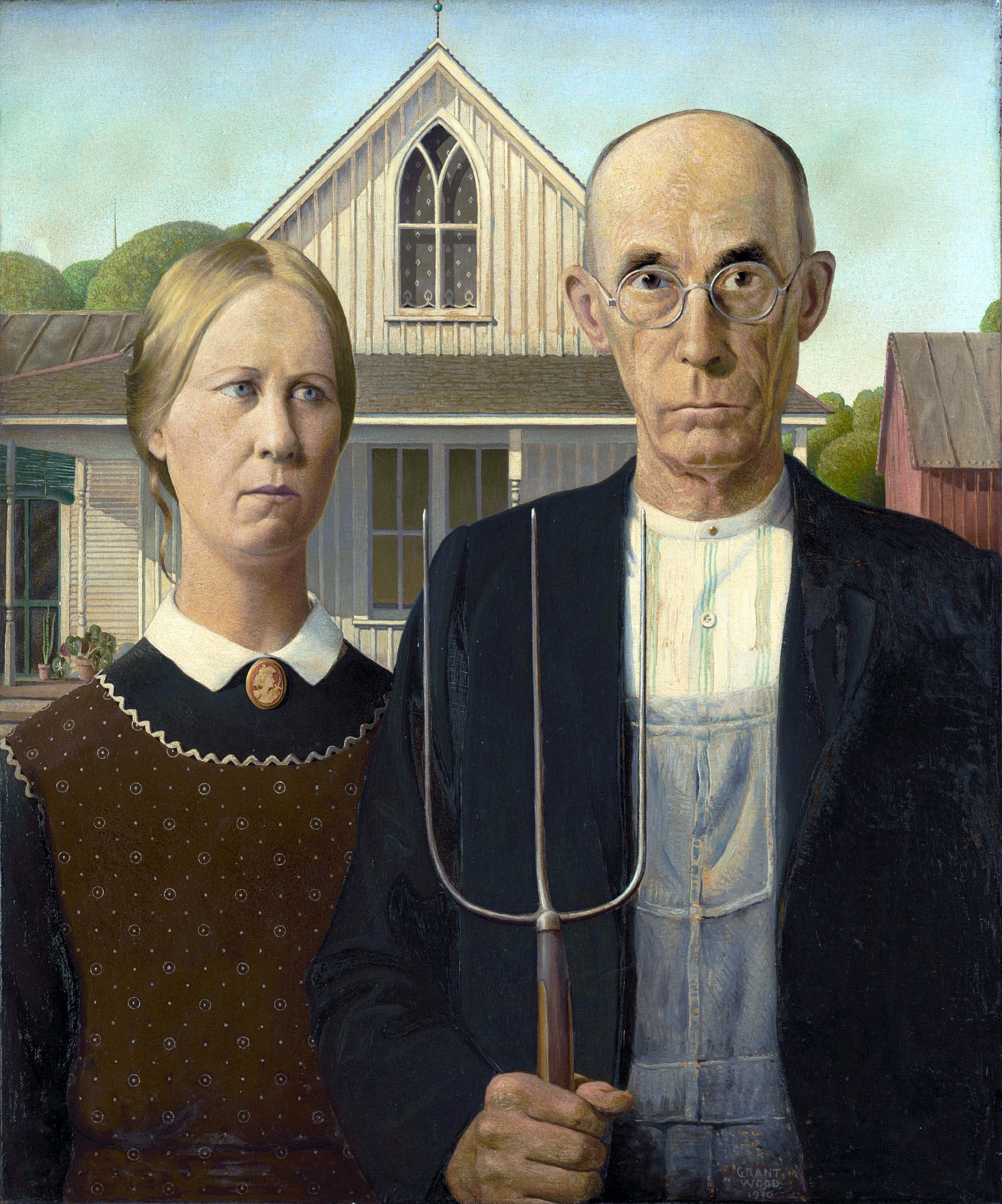

York is the port of entry for so many ancestors of red-state citizens is good barb to use against unsuspecting New York haters. Like these guys…

Benign and incidental as it may be,

the fact that the sidewalks of New York constitute the earliest, most

sepia-toned memories of America that most European immigrants can call

up is worth pondering. Maybe that pitchforked old man in “American Gothic,” you

know the one,

is thinking about the hurdy-gurdy man on the corner Hester

and Bowery in the Lower East Side, not the wheat and milk-cows of the prairie. Maybe the capitals of

the world really are our fathers.

If so, I’m that much closer to getting why my uncles love Bruce

Springsteen, why his ballads of sainthood in the neighborhoods of the Jersey Shore ring so true them, boys who grew up in the Irish-Italian ward of Kansas

City. There may have still been some traces of the blue-collar, urban

sensibility of Springsteen’s lyrics in the streets of the northeast Kansas

City when my uncles were young. Maybe sidewalks of New

York once extended all the way out to middle America.

It's the suburbs that severed the link to New York, that repackaged our stereoscopic birthrights into the bright lights, big city skyline posters and the “I <3 NY” T-shirts we all ignored on our way to the Orange Julius stand.

It's the suburbs that severed the link to New York, that repackaged our stereoscopic birthrights into the bright lights, big city skyline posters and the “I <3 NY” T-shirts we all ignored on our way to the Orange Julius stand.

The ties that bind red and blue America are buried somewhere beneath the shopping malls of our youths.